In an effort to limit the risk of spreading COVID-19, the majority of governments have temporarily closed their educational institutions, affecting nearly 90% of learners worldwide. How are educational systems and communities organizing themselves to ensure educational continuity in a world facing an unprecedented pandemic?

In an effort to limit the risk of spreading COVID-19, the majority of governments have temporarily closed their educational institutions, affecting nearly 90% of learners worldwide. How are educational systems and communities organizing themselves to ensure educational continuity in a world facing an unprecedented pandemic?

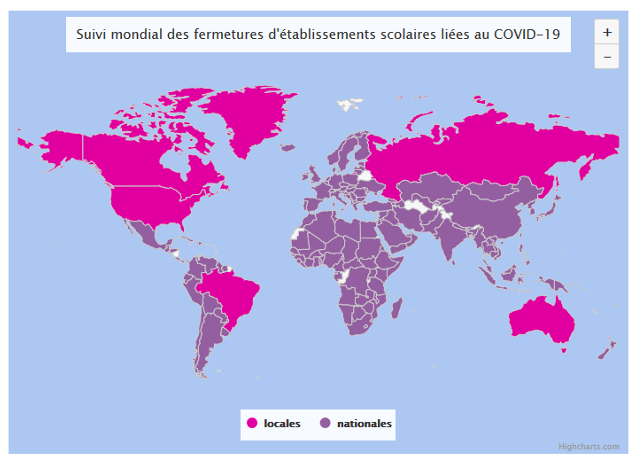

UNESCO Global monitoring of school closures caused by Covid-19

Virtual platforms, TV shows, online health advice: educational communities are mobilizing

As an immediate response to the widespread school closures, UNESCO has set up a working group to provide advice and technical assistance to governments on how to maintain the education of out-of-school students. It has also formed a global coalition “COVID-19 for Education”, which brings together multilateral partners including private sector actors. “The current situation poses immense challenges for countries to be able to provide uninterrupted learning for all children and young people in an equitable manner,” says Audrey Azoulay, Director-General of UNESCO.

In order to enable continued learning and to maintain a link with students, many countries have developed distance education alternatives. These different tools and resources aim to help parents, teachers and school administrators in supporting students or providing psychosocial support during this period of crisis. Education International (EI), the largest global union federation in the field of education, is closely following the developments of the crisis and its impact on education systems. Through its 384 organizations around the world, EI is collecting on a dedicated platform the difficulties encountered and responses made by communities to maintain quality education for all, as well as guiding principles to respond to the crisis. Some examples of these initiatives at the international level.

In Serbia, the teachers’ union reports a prompt adapting of educators to distance education through the use of digital technology and specialised television programmes. Online courses from primary school to university were prepared in a very short time, and from 23 March courses in minority languages and for migrant children also began. These efforts are being welcomed by students and their parents, who, according to Borka Visnic, Head of the International Cooperation of the Teachers’ Union of Serbia, “are becoming more involved and aware of the importance of teaching and the teaching profession“.

Educators in Nordic countries are appropriating digital tools to help stop the spread of COVID-19. In Denmark, different teachers’ unions have set up information websites, focusing on the rights of education staff and providing health advice, but also resources on how to interact with children. Arrangements for students with special needs’ containment are also in place.

Education unions in Argentina are collaborating with the Ministry of Education to create educational content accessible to all students through the platform “Seguimos Educando” (“Let’s keep on educating”). Various initiatives are being developed or considered, ranging from virtual platforms to television, to the preparation and distribution of printed educational materials, in order to reach all populations, including those with no digital means, to prevent social inequalities from increasing.

In Switzerland, teachers who are members of the Syndicat des Enseignants Romands, visit their pupils’ homes every week to give parents study documents. This is a way of ensuring that all children, especially those in vulnerable situations, have access to resources and to maintain a link between schools and families.

The limits of distance learning

Aside from the issue of teacher’s training in digital tools, inequalities regarding technologies deprive a large number of students of the opportunity to continue their learning.In addition to the difficulties linked to Internet access or the instability of electrical installations in some countries, families’ access to computer equipment is critical. In Senegal, Ghana or Burkina Faso, for example, the norm will be mobile phones rather than laptops. School closures thus tend to reinforce inequalities. Privileged students often have better access to these tools and benefit from family support that provides a stable working environment. For underprivileged students, the lack of technical equipment and pedagogical support can aggravate academic delay and ultimately create a risk of school drop-out.

Furthermore, the exposure of learners’ and educators’ personal data and information to online attacks is also an issue. Lastly, although educational programmes on television or radio are available in some countries, their effectiveness is limited compared to the coverage of formal programmes by levels.

Distance learning systems, while limiting the impact of the covid-19 crisis on education, remain temporary alternatives that can never replace learning and teaching in the classroom. Education unions are already urging national administrations to reinforce the means of public institutions to best compensate for the pedagogical damage caused by this crisis when it is over.