Layoffs, increases in workload, performance standards, workplace optimisation, outsourcing, job instability, etc. In 2018, the CSQ has launched a major campaign to raise the awareness of its members and the wider community about these unhealthy management practices that are causing health problems, both physical and psychological.

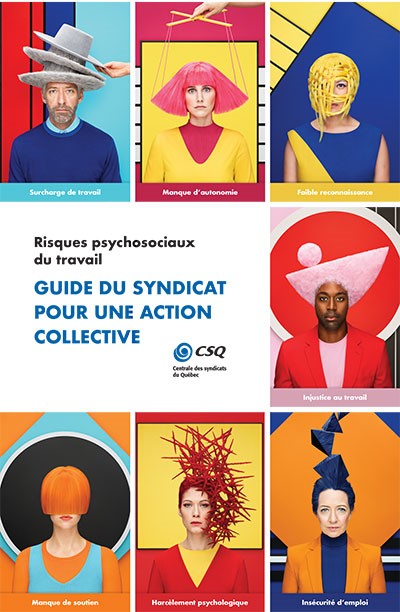

Taking as its slogan “It’s not all in your head”, the campaign depends on original and impactful stories to provide examples of the very real psychosocial risk factors in the workplace that can make people unwell.

Layoffs, increases in workload, performance standards, workplace optimisation, outsourcing, job instability, etc. In 2018, the CSQ (Quebec Union Organization) has launched a major campaign to raise the awareness of its members and the wider community about these unhealthy management practices that are causing health problems, both physical and psychological.

Taking as its slogan “It’s not all in your head”, the campaign depends on original and impactful stories to provide examples of the very real psychosocial risk factors in the workplace that can make people unwell.

As well as evaluating management practices that make workers doubt their skills, the campaign encourages workers to become part of a process of collective action and to act by telling their union about their circumstances.

An article by Pierre Lefebvre published in the CSQ magazine in November 2018 (in French).

AGGRAVATING RISK FACTORS

Despite some exceptions, the scientific literature is almost unanimous in its view of what may constitute risk factors. In Quebec, the Institut national de santé publique (INSPQ, the National Public Health Institute) has identified the following seven factors:

- Heavy workload and time pressures;

- Low levels of acknowledgement of efforts and results;

- Lack of autonomy and influence at work;

- Job insecurity;

- Low levels of support from colleagues and managers;

- Violence and psychological harassment;

- A lack of fairness within the organisation.

Luc Bouchard and Matthew Gapmann, the CSQ’s occupational health and safety advisors, explain that, over time, these risk factors can cause people serious health problems, including headaches, difficulty concentrating, memory loss, irritability, fatigue, digestive disorders, exhaustion, cardiovascular disease, and depression. The risk factors can reinforce each other and make each other worse, increasing their impact on the health of anyone affected.

“For example, job insecurity and instability can create a climate of violence and psychological harassment by placing people in a situation where they are competing for the jobs available, thereby further undermining the social support needed from colleagues. Similarly, a heavy workload can create a feeling of unfairness within the organisation, when the effort invested in doing high quality work is not given due recognition”, says Luc Bouchard.

POINTING THE FINGER AT THE REAL CULPRIT

The campaign points the finger at the real culprit: an unhealthy work environment that can be changed by collective action.

“Work making people unwell is a phenomenon that is having an impact on increasing numbers of workers. Too often, these people mistakenly believe that they are the source of their illness. Other people end up questioning their skills – because they are unable to adjust to or comply with the unreasonable demands of their job”, says Sonia Ethier, the president of the CSQ.

“And, when they go off sick, it is not uncommon for an adjustment disorder to be diagnosed, as if people are expected to be able to adjust to harassment, violence and the unreasonable rhythm and intensity of an excessive workload. It’s completely absurd”, she says.

THE LIMITS OF LEGAL AND INDIVIDUAL SOLUTIONS

A lot of people find individual solutions to the difficulties they experience, such as voluntarily reducing the number of hours they work or taking unpaid leave or leave with deferred salary.

Although these solutions may give people a much-needed break, they do not tackle the root cause of the problem – the way work is organised. They just act as a sticking plaster on an open wound. They might even contribute to an increase in risk, by expanding the number of precarious replacement jobs or by adding to the workload of those people who remain in their jobs, for example.

Some collective agreements, particularly in the health and social services sector, include provisions that allow employees to challenge excessive workload through a grievance procedure.

“However, that requires a significant level of proof and a ‘normal’ workload isn’t defined. That’s decided by the arbitrator. The other collective agreements in force in the sectors we cover contain few or no guidelines relating to psychosocial risk factors, apart from the right to a work environment free from psychological harassment. If there are no specific provisions, it’s unlikely a grievance would be upheld and, even if you have a good chance of winning, it takes a very long time”, says Matthew Gapmann.

COLLECTIVE ACTION TO BRING ABOUT CHANGE

Isn’t trade unionism all about developing an approach based on the collective defence of workers’ interests? Although collective bargaining is the trade union movement’s preferred strategy, the large scale of the structures in the public and semi-public sectors makes it difficult to find suitable solutions to solve problems that may, for example, come from a manager’s pedantic bureaucratic management style. The specific characteristics of every workplace therefore mean that we have to focus on a workplace at its own local scale.

“There is no single solution that addresses all of the difficulties people experience. Of course, the union has an important overall role to play in encouraging an employer to adopt organisational practices that benefit employee health, put people ahead of performance and productivity goals, and prioritise managing people as resources rather than simply managing human resources ”, says Sonia Ethier.

She makes it clear that collective action helps support members who are facing psychosocial risks, so that they can act together at local level to eliminate them or reduce their impact. Research has also clearly highlighted the importance of collective action to combat this phenomenon.

“Our campaign exemplifies the type of union action our congress asked for in 2015, and falls within the framework of action that we adopted at our congress in June 2018, which allows us to act collectively to oppose work that is organised in an unhealthy way. Together, we have the ability to act: that’s what our campaign emphasises. And it’s so true: union history is full of examples”, says the union leader.

UNION GUIDE TO COLLECTIVE ACTION / Excessive workload / Lack of autonomy / Low levels of acknowledgement / Psychosocial risk factors in the workplace / Unfairness at work / Lack of support / Psychological harassment / Job insecurity

USEFUL TOOLS

The CSQ has produced leaflets about the seven risk factors, which describe the signs or indicators for each risk, along with the features found in a healthy and risk-free workplace. The leaflets also include a request for members who have suffered from problems of this kind to let their union know so that the union is aware of what is going on and can provide support.

Note too that a guide for unions offers a simple six-step process for anyone interested in taking action and for other people in the workplace who may be experiencing the same problem.

The union is requested to bring these people together so that they can work together to identify the context and the problems they have encountered, highlight the harmful impact on their health, clarify the impact on their work, suggest actions to rectify the situation and, finally, carry out the actions required to put the solutions into effect.

EMPLOYERS AND THEIR OBLIGATIONS

In a unionised workplace, organising work is the last remaining part of employers’ right to manage, which explains why they are reluctant to discuss it. However, employers have occupational health and safety obligations that affect how work is organised.

In fact, according to the Act Respecting Occupational Health And Safety[1], employers have a general obligation to take the necessary measures to protect the health, in the broadest sense of the word, and ensure the safety and physical well-being, of their workers. In particular, they must use methods and techniques intended for the identification, control and elimination of risks to the health and safety of workers. They must also ensure that the way that work is organised and the working procedures and techniques used to carry it out are safe and do not adversely affect the health of workers.

TO FIND OUT MORE

- The CSQ website, health and safety at work: lacsq.org/sst.

- Website of the Institut national de santé publique du Québec (INSPQ): inspq.qc.ca/publications/2372.

- Website of the Chaire en gestion de la santé organisationnelle et de la sécurité du travail (Centre for Managing Health in Organisations and Safety at Work), at Université Laval: cgsst.com.

An article by Pierre Lefebvre published in the CSQ magazine in November 2018 (in French).

[VIDEO::https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mhg4tPxWNQI::normal]

[VIDEO::https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NpvS8oSVXDU::normal]

[VIDEO::https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pfa-oQ7xQ1Q::normal]

[VIDEO::https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EQleGLu1B_Q::normal]